Erodium cicutarium, usually known as red-stemmed filaree or common stork’s-bill, is native to the Mediterranean region and was introduced to California in the eighteenth century. There is archaeological evidence for the presence of red-stemmed filaree in adobe bricks from the Spanish mission at Jolon in San Luis Obispo County. In the Central Valley of California, pollen from filaree has been identified in layers of mud dating to the 1700s.

There is evidence, in fact, that filaree invaded Alta California from Baja California before the arrival of Spanish livestock in 1769 (Mensing, 2006).

Why do I care?

Here, look.

This is filaree.

What you’re looking at is a herbaceous annual (in some warmer regions it is considered a biennial). I am going to be calling it a perennial here at RSF. I’ll explain.

Filaree is called an invasive weed in the deserts and arid grasslands of the United States. Calflora.org (my serious go-to for native plants) has it listed as invasive, not native in red with caps. That’s some strong indicator of what California botanists think of “invasive weeds.”

Plant migrations are interesting. When a plant has no immediate and appealing food value (even simple culinary value, as in spices) we tend to think of the plants as weeds or even as a nuisance.

I’m guilty.

While J3 and B were out shooting some hoops I was using a Magic shovel to uproot filaree in my front yard. I’ve already cleared most of it from the orchard. I don’t own a tractor. (Honestly, I’d like to own a small one, permaculture values aside. Go ahead, call me a hypocrite. And then try eking some food out of this high desert.)

And, yes, there really is a Magic shovel. They are great in archaeology for getting nice square sides on units. They are also very nice for backfilling. Sorry, I can’t find a link. That’s just sad.

So I’m yanking by hand and shoveling like a maniac. All the while I’m saying, “Any plant that can grow in the midwinter and freaking bloom when the nights are freezing is going to take over the world.”

Every one of my kids, when they were little, would gather handfuls of these little pink to purple flowers and lovingly bring them to me. I have a small collection of colorful little handblown Fenton glass vases from my mother that I used to put these precious flower offerings into. One child so sweetly told me “look how tiny and they’re so beautiful…” Yes, they were, seen through the eyes of a child in which everything is scared. And then I’d feel guilty as I went out to the orchard and tore the plants out by the handful.

Some Fenton glass vases.

Picture a couple dozen or so of these in a vase.

Filaree in flower.

Are they weeds (plants where people don’t want them) or are they food?

Naturalized annuals such as red-stem filaree (Erodium cicutarium), curly dock (Rumex hymenosepalus), wild oat (Avena spp.), various brome grasses(Bromus spp.), and wild mustards (Brassica spp.) became successfully established in California deserts and grasslands with the spread of Spanish livestock in Alta California, maybe before that time (Crosby, 1986; Mensing, 2006). Many early Euro-American explorers, settlers, and ethnobotanists have mentioned these species. Quite often they are mentioned because Native Americans had found uses for these plants and told the newcomers.

Rumex, Curly Dock, Canaigre, Wild Rhubarb

Brome grasses – a fire hazard – around fallen Joshua Tree.

Wild Mustard Flower

Filaree, in particular, was consumed by people. It’s edible, especially when picked young and tastes a bit like parsley. So, right now, I could go out and harvest any number of these and toss them into my salad.

Reportedly, all stems and leaves can be consumed raw or cooked. Animals enjoy eating it. My chickens like it. Medicinally it is a diuretic, astringent, and anti-inflammatory herb. I personally would not want to eat the older, hairy stems of this plant. To me, hair on plants (at least if it doesn’t wash away, like from a garden zucchini) means trouble. On the other hand I can see putting some of the young leaves into my salads or stews and soups.

About botanical terms.

There are technical botanical problems with the term “invasive species” and sociocultural problems with the frequently still used term “invasive alien species.” Take note.

Tamarisk is often described as an introduced species.

As far as terminology, I do prefer the term migrating or migrant species because that’s what plants do. That’s what they’ve always done; they migrate.

The tamarisk or salt cedar, Tamarix , is a particularly difficult case in the United States Southwest and California where it clogs up watercourses and adds to soil salinity.

Thicket of tamarisk and willows at a spring, March.

Here in the southwestern Mojave, we’re watching the Mojave River ecosystem become congested with tamarisk and we call it nonnative/invasive. Problems with it? It eliminates habitat needed by many regional birds and other animals; it out-competes the local cottonwoods, essentially threatening the cottonwood woodlands that have been here for centuries/millennia; it sucks up groundwater like crazy eliminating former marshy areas where indigenous people have harvested rushes for their basketry; it concentrates salt in its leaves and leaves the soil around it salt-laden and not a happy place for many regional plants.

So.

Tamarisk was brought to this desert 100-150 years ago as a windbreak for many homesteads. It’s fast growing and all things not considered, it made decent windbreaks. It just didn’t want to stay put.

Next to the Mojave River bed, many tamarisk, few cottonwoods.

I could plant it here as a windbreak. It would be very happy. I’d have my quick and easy windbreak. All along Highway 18 and 395 older homesteads have tamarisk windbreaks. It is thriving along the Mojave River. But I just cannot bring myself to do it.

In other riparian zones in the North American West there have been tamarisk eradication efforts. People are talking about it now, out here, but nothing much is happening yet.

I suppose that’s the bad of migrating plants. New plants can mess with established ecosystems.

I think we may need to embrace some of these migrant plants. It’s what people have always done. In my battle with filaree, I’m really beginning to understand how new plants get a foothold, how they continue to adapt until they are well-established, and how they overpower our feeble human efforts. Feeble because we can destroy the land and the soil by poisoning the “weeds.” We can spend all of our time uprooting them, to the neglect of our other food plants. Why not investigate what good they may contribute?

For instance, I’ve been seeing multiple articles on the internet touting the medicinal value of the ubiquitous weed of my childhood, plantain. I cannot even tell you the number of these little and tenacious weeds I was enlisted to pull from my mother’s flower beds in northwestern Ohio. As a child I thought they were nasty. Apparently, as an ethnobotanist, I need to reconsider. They are good for us. Had I only known.

Now for more good.

There’s the thought that the ubiquitous Mojave Desert creosote bush traveled north at the end of the Pleistocene. It’s considered native. What does it take to become native? 10-12 thousand years? A couple hundred? 20 years?

Creosote bush has amazing medicinal properties; it also contains some toxic alkaloids. No one I know who is interested native plant communities in the Mojave Desert would want to send it back, necessarily. It has established itself. Did it wreak havoc on the ecosystem that existed in this semi-arid desert as it migrated northward?

We look at the newest riparian invader, tamarisk, and acknowledge that it is currently decreasing native biodiversity. Did creosote, so much a part of our desert experience, do the same thing, initially?

And now on to another happy migrant plant.

California Fan Palms (Washingtonia filifera) is a feature of southern and Baja California oases, springs, and seeps and vast stretches of southern California urban and suburban landscapes. This major food, fiber, and construction resource for indigenous people was pretty likely introduced to southern California from points south. There are ethnohistorical accounts and there is archaeological evidence that fan palms were once moved ever-further north by enterprising indigenous horticulturists.

These palms were a major resource. They are pretty hearty, nice to look at, and now they are a total symbol for southern CA. In parts of southern California, indigenous people still enjoy eating their fruit. Are they native to the southern Mojave Desert? Probably not, but we now consider them to be. They are a piece of the whole fabric now.

California Fan Palms at Oasis of Mara, 29 Palms, CA.

So what to do?

Back to the filaree.

Each little filaree plant can produce between 2,000-10,000 seeds. See their pointy little seeds capsules? They are ejected from the plant at maturity, then dispersed by driving themselves into the ground, burrowing into animal fur or even bird feathers, or being carried away by water. The seeds can survive in harsh environments and remain viable in the soil for many years.

Check out the barbed seeds pods.

Brassica spp., our wild mustards, pop up in abundance in my orchard every year and filaree — everywhere, every year, all year. That’s why I call them perennial. They simply do not die back.

Mediterranean and many Asian plant species from semi-arid regions are generally pre-adapted to much of California’s climate which aids their dispersal throughout the state. These are some very hearty plants because they are obviously ready for the high desert.

Now with global climate change having an impact on California, including the desert regions, I’m seeing some changes in the filaree, at least. Most of the regional plant books I have say filaree begins its season in the high desert as early as February. And most of them say it flowers from then to about May.

In warmer regions of California, the plant may flower through most of the year.

Here, at RSF I’ve noticed that it doesn’t die back anymore until (1) the hottest of summer weeks; (2) the very first hard freezes in the fall/winter. If then. Then immediately, after a die-back, especially after some rainy days, it will begin to grow and flower rapidly. Right now we haven’t had rain for a while, the nights are still reaching freezing often, and we’re awash in filaree.

Even if I began using it regularly as a salad and pot herb, even if I let the chickens out to eat as much as they liked, even then it would be taking over the place.

I still can get into the “yank out the invader” mindset. I did this afternoon. I also thought about getting goats again and hoping they’d enjoy it. I then thought about getting some geese again because I know they’d eat it. But. I’m not really ready for the responsibility of caring for those animals yet. Not yet.

Filaree and wild mustard and other prolific plants don’t know they are “out of place” (permaculturalist David Holmgren calls weeds “plants out of place”). I’ve been researching a few of the more prolific migrant plants that grow here at RSF. Using an agroecological framework, two of these plants may be able to become a useful part of the farm ecosystem. Filaree and wild mustard. Wild mustard concerns me because I really don’t want a part of my land to look like this:

It’s taking over the world.

It could and it might.

Wild mustards are being eradicated in farmers’ fields in California because they are so opportunistic they will take over entire fields of crops. Bear in mind those fields tend to be much larger than the whole of RSF. And I’m not growing here for commercial purposes, not now anyway. RSF is for learning and for experimenting, so I can usually afford to make some mistakes that my friends who are commercial farmers can’t.

Some things I’ve learned about these plants:

RSF filaree harbors ladybugs, a definite plus for any high desert farmers.

Goats like and thrive on the wild mustards.

In the parts of the world the mustard plants come from they have been used as food and medicinals.

Filaree can be (and is) used in the same ways.

Both have flowers that attract bees. The almost year-round flowering of the filaree is a plus for beekeeping in the desert.

I wonder what I might be missing in my knowledge of filaree that the ladybugs know.

And I know that early this spring I will be taking wild mustard that grows in my orchard and tossing it into my salads and maybe into a stir fry like spinach. Rich in vitamins A and C, calcium and iron, right? And free. And right out the back door.

Wild Mustard Leaves

David Holmgren questions what he calls “the nativist orthodoxy” about migrating plant species.

Given my experiences gardening/farming in the Mojave Desert, I think we desert farmers would do well to heed his words.

“… it is incumbent on those with a more balanced and holistic (ecological) perspective to articulate the positive aspects of plant naturalizations. The greatest good than might flow from this articulation is the protection and study of advanced examples of novel ecosystems.”

I have so many questions and no answers about this ecosystem in transition. But I love throwing myself into the mix.

What else is there to do?

Crosby, Alfred W. (1986). Ecological imperialism: The biological expansion of Europe, 900-1900. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Mensing, Scott. (2006). The History of Oak Woodlands in California, Part II: The Native American and Historic Period. The California Geographer. Volume 46.

Suggested reading:

Medicinal Plants of the Mountain West by Michael Moore

Medicinal Plants of the Pacific West

Medicinal Plants of the Desert and Canyon West

This one is short, to the point, and really great:

Los Remedios: Traditional Herbal Remedies of the Southwest

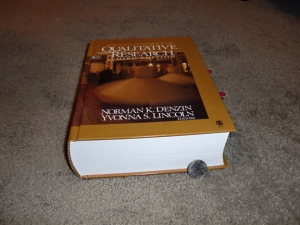

There’s always The Big Book; this got me through my master’s thesis and my dissertation and I have consulted it so many times in technical writing:

Native American Ethnobotany by Daniel E. Moerman